A microbiome silver bullet for honey bees ?

?

The January 30, 2020 issue of Science includes an article on genetically modified honey bee gut bacteria tailored to induce host RNA interference (RNAi)–based defense against varroa mites that is effective, long-term, potentially cheap, and easy to apply. By altering one of the bacteria in the honey bee gut, a bacteria not known in other environments, the varroa mites take in RNA -- essentially, genetic assembly instructions -- that damage their own ability to survive and reproduce. This area of research is closely related to Dr. Samuel Ramsey's ground breaking insights into the nature and mechanics of varroa biology and nutrition. Mites exposed to honey bees with the altered bacteria within their biome were 70% more likely to die than those in control honey bees.

Eating Nectar is Harder than You Might Think

Regurgitation is an important consideration when it comes to the process of pollination.

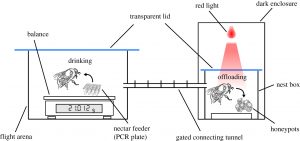

Just like honey bees, bumblebees weigh all the variables when judging a nectar source: flight distance, the shape of the petals and how sugar-rich the nectar is, even more. But according to a study published February 4 in the Journal of the Royal Society Interface, there’s another variable the bees may be considering: How fast can they barf it back up?

The team gave the bees access to solutions at three strengths: 35 percent, 50 percent and 65 percent, and spent hours watching individual bees forage, timing how long it took for the different concentrations to go down the hatch and then come back up again.They found that high concentrations slowed vomiting considerably — more than they slowed down drinking. While offloading a 35 percent solution only took four or five seconds, the process for a 65 percent solution could go on for nearly half a minute. The data they collected showed that bumblebees may prefer nectar concentrations with 3 or 4 percent less sugar than previously anticipated, in order to avoid being slowed down too much during regurgitation. This can influence which plants bees choose for pollination, and help farmers plan pollination services.

Almond Pollination and Honey Bees in the News

In media outlets across the United States and Europe, the continent-wide movement of honey bee colonies to almonds is coming under critical scrutiny. The report from The Guardian ("Like Sending Bees to War") which was later picked up by major media outlets across the country, focuses on the use of pesticides on the almond crop, the large numbers of colonies that must be moved to pollinate it, the enhanced exposure to pests and diseases this concentration brings, and the high water use this crop requires. Beekeepers who rely on almond contracts were quoted as concerned but unwilling to cease the activity, while beekeepers who identified as organic were more critical. A new certification, the BeeBetter Seal from Xerces seeks to offer a way for consumers and others to identify almond products that are more supportive of biodiversity for native and honey bee health.

Bt for Wax Moth Control to be Registered by EPA

Bt for Wax Moth Control to be Registered by EPA

(Bacillus thuringiensis, subsp. aizawai strain ABTS 1857)

EPA is proposing to register a pesticide product containing Bacillus thuringiensis, subsp. aizawai strain ABTS 1857 (Bta ABTS 1857) to prevent and control wax moths in beehives. This product offers beekeepers a new tool against destructive wax moth larvae.

The active ingredient in this pesticide product (Bta ABTS 1857) is part of a large group of bacteria, Bacillus thuringiensis, that occur naturally in soil. Bta ABTS 1857 controls wax moth infestations by producing a crystallized protein that is toxic to wax moth larvae. To use this product, commercial and hobbyist beekeepers would apply a dilute solution of Bta ABTS 1857 to empty honeycomb frames prior to winter storage. When wax moth larvae attempt to feed on the honeycomb, they would also ingest some Bta ABTS 1857, which will release a protein into the larva’s digestive system that attaches to the gut, eventually causing it to rupture. Risk assessments and other documents related to the proposed decision are also available.

County-level analysis: rapidly shifting insecticide hazard to honey bees

County-level analysis: rapidly shifting insecticide hazard to honey bees

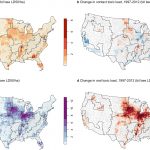

In a January 21, 2020 article in Scientific Reports researchers integrated several public datasets to generate county-level annual estimates of total ‘bee toxic load’ (honey bee lethal doses) for insecticides applied in the US between 1997–2012, calculated separately for oral and contact toxicity. While the contact-based bee toxic load remained relatively steady, oral-based bee toxic load increased roughly 9-fold, with reductions in application outweighed by increases in potency and extent. This pattern varied markedly by region, with the greatest increase seen in Heartland (121-fold increase), likely driven by use of neonicotinoid seed treatments in corn and soybean. (click to expand image)

Too Many City Bees?

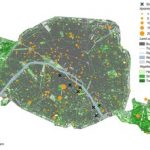

For a decade or more, cities have been perceived as shelters for pollinators because of low pesticide exposure and high floral diversity, but a study from Paris in PlosOne titled "Wild pollinator activity negatively related to honey bee colony densities in urban context" found that visits from wild pollinators (among them bumblebees, solitary bees, and beetles) were reduced when managed colonies were located within 1 kilometer. More troubling, honey bees preferred to visit non-native plant species, reducing pollination support for native plants in the urban areas studied. The study authors advocate mitigating practices where high density urban beekeeping is practiced, but suggest further study to deepen our knowledge of how that might work.

For a decade or more, cities have been perceived as shelters for pollinators because of low pesticide exposure and high floral diversity, but a study from Paris in PlosOne titled "Wild pollinator activity negatively related to honey bee colony densities in urban context" found that visits from wild pollinators (among them bumblebees, solitary bees, and beetles) were reduced when managed colonies were located within 1 kilometer. More troubling, honey bees preferred to visit non-native plant species, reducing pollination support for native plants in the urban areas studied. The study authors advocate mitigating practices where high density urban beekeeping is practiced, but suggest further study to deepen our knowledge of how that might work.