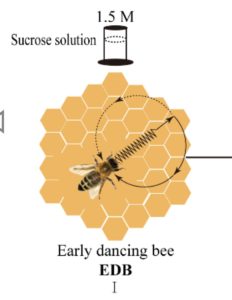

Honey bees increase social distance when facing Varroa

A recent study by Michelina Pusceddu of the University of Sassari, in Italy, and six colleagues found that honeybees in hives infected by parasites implement their own form of social distancing. To determine how Varroa changes bees’ behaviour, the authors set up six colonies, half of which were infected with the mite. They studied two common activities: the “waggle dance”, which forager bees perform to communicate the site of a newly discovered food source, and “allogrooming”, when bees clean debris or parasites (including mites) from each other’s bodies. The differences between the colonies were striking. In the Varroa-free group, waggle dances and allogrooming both occurred throughout the hive. By contrast, in infected colonies, most waggling occurred by the sides of the entrance, keeping potentially infected foragers far from brood cells. Conversely, allogrooming was concentrated in the centre of the hive, where parasite removal had the greatest impact. [More info]

A recent study by Michelina Pusceddu of the University of Sassari, in Italy, and six colleagues found that honeybees in hives infected by parasites implement their own form of social distancing. To determine how Varroa changes bees’ behaviour, the authors set up six colonies, half of which were infected with the mite. They studied two common activities: the “waggle dance”, which forager bees perform to communicate the site of a newly discovered food source, and “allogrooming”, when bees clean debris or parasites (including mites) from each other’s bodies. The differences between the colonies were striking. In the Varroa-free group, waggle dances and allogrooming both occurred throughout the hive. By contrast, in infected colonies, most waggling occurred by the sides of the entrance, keeping potentially infected foragers far from brood cells. Conversely, allogrooming was concentrated in the centre of the hive, where parasite removal had the greatest impact. [More info]

The Bees That Eat Corpses

A November 2021 article in Microbial Biology asks, "Why Did the Bee Eat the Chicken?" (this is a direct quote). In it, a team led by scientists Laura Figueroa and Jessica Maccaro of Cornell and USC/Riverside explore the biome of bees that switched back to being carnivores from the vegetarian lifestyle of the vast majority of bees. Researchers found that vulture bees lost some ancestral “core” microbes, retained others, and entered into novel associations with acidophilic microbes, which have similarly been found in other carrion-feeding animals such as vultures, these bees’ namesake. There is an accurate, entertaining and short Youtube video available from SciShow that digs into how the bee microbiome works, and is worth a view!

Learning and Inspiration from Forest Bees

Brand new from Princeton University Press, Wild Honey Bees is a beautiful scientific and photographic study of German forest bees that offers insights even to beekeepers who have read 'em all.

While the astonishing macro photography will reach into (and beyond) areas familiar to keepers of managed bees, the authors, Into Arndt and Jürgen Tautz, capture bees working in natural settings that can inform (and yes, amaze) those of us working in backyard or urban settings. As many of us grapple with finding practices that support bees' evolutionary adaptations to pets and disease control, the book describes an entire ecosystem that works with the bees (as they work) to create sustainable, remarkable, inspiring natural systems of bee health. What if we could have book scorpions riding the backs of our bees, right?

Understanding the Waggle Dance from the Inside: Looking at RNA

Scientists from Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (China) and University Toulouse III (France) have collaborated to study the regulatory mechanisms underlying the waggle dance. Though the dance itself has been deeply studied, and of course decoded, it is not well understood how the bees' brains produce and are able to interpret the dance.

By varying the quality of the nutrition given to bees, the scientists were able to alter the quality and effectiveness of their communication. This points at the role of RNA (specifically non-coding RNA) on the target genes. The results indicated that lncRNAs in brains of waggle dancers and non-dancing bees exhibited significant differences.

In studies of humans, it has been shown that poor nutrition or other environmental variables can inhibit or damage gene expression: a function of the way in which RNA dictates how genes can perform.

The results of RNA sequencing indicated that a total of 2877 lncRNAs and 9647 mRNAs were detected from honey bee brains. A first in this area, the study is expected to open a new pathway to research on the relationship of behavior and the brain.

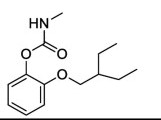

Testing new compounds for efficacy against Varroa and safety to honey bees

A team led by Cameron Jack of the University of Florida led a study on new acaricides (chemicals used for control of Varroa destructor), noting that increased resistance to existing treatments drives the search for new, safe alternatives. The team looked at toxicity to mites (desired) versus to honeybees (undesirable) and assessed each.

Among the chemicals tried, amitraz remained the most toxic for varroa, but one of the "carbamate" compounds was found to be almost has toxic to varroa but much less so to honey bees. Additional testing is required to determine if 2-(2-ethylbutoxy)phenyl methylcarbamate can be used as an effective Varroa control.