Sunflowers Linked to Reduced Varroa Mite Infestations in Honey Bees

A December article in the Journal of Economic Entomology by a team led by Evan Palmer-Young, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bee Research Lab, adds to Dr. Sammy Ramsey's work on varroa biology by describing how nutrition may impact the viability of the mites. Sunflower pollen and nectars are protein poor and not the best nutritional support for bees, located near sunflower cropland had lower mite levels—even when the total land cover by sunflowers was scant. The researchers aren't ready to suggest major changes in land use, but Dr. Palmer-Young hazards, “If sunflowers are as big of a factor in mite infestation as indicated by our landscape-level correlations … having a few more acres of sunflower within a mile or two of apiaries could bring colonies below the infestation levels that require treatment of hives with acaracides.” [More info]

US Government Approves First Vaccine for Honeybees

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has granted a conditional license for a vaccine created by Dalan Animal Health, a US biotech company, to help protect honeybees from American foulbrood disease. The vaccine technology exposes queen bees to inactive (i.e., “dead”) bacteria, which enables the larvae hatched in the hive to resist infection. The vaccine is mixed into queen candy (photo), which the queen ingests. Fundamental to this vaccine is scientific research over recent years that has proved that workers can inherit immune response from their queens. [More info]

The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) has granted a conditional license for a vaccine created by Dalan Animal Health, a US biotech company, to help protect honeybees from American foulbrood disease. The vaccine technology exposes queen bees to inactive (i.e., “dead”) bacteria, which enables the larvae hatched in the hive to resist infection. The vaccine is mixed into queen candy (photo), which the queen ingests. Fundamental to this vaccine is scientific research over recent years that has proved that workers can inherit immune response from their queens. [More info]

Catch Up On Bee Research!

The Journal of Insect Science (in partnership with the American Association of Professional Apiculturists) has put together a free, one-stop shop for you to look at articles "Investigating Fundamental and Applied Aspects of Honey Bee Biology." Compiled by Hongmei Li-Byarlay, Margarita Lopez-Uribe, and Michael Simone-Finstrom, titles include Jack and Ellis on IPM, Metz and Tarpy on Drone quality, Arathi and Bernklau on pesticide exposure, Shanahan on bees in industrial agriculture, and so much more. The Journal of Insect Science is published by the Entomological Society of America. [More info]

The Journal of Insect Science (in partnership with the American Association of Professional Apiculturists) has put together a free, one-stop shop for you to look at articles "Investigating Fundamental and Applied Aspects of Honey Bee Biology." Compiled by Hongmei Li-Byarlay, Margarita Lopez-Uribe, and Michael Simone-Finstrom, titles include Jack and Ellis on IPM, Metz and Tarpy on Drone quality, Arathi and Bernklau on pesticide exposure, Shanahan on bees in industrial agriculture, and so much more. The Journal of Insect Science is published by the Entomological Society of America. [More info]

Not Exactly News, But More Proof?

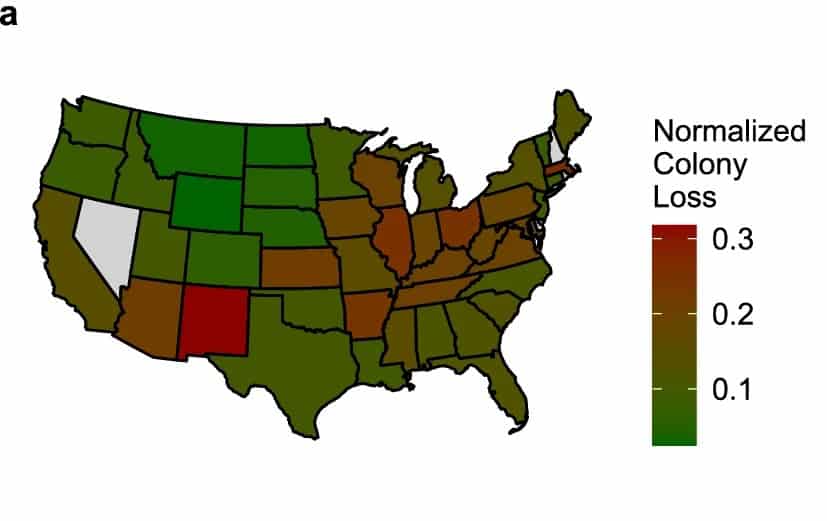

A new study led by Penn State researchers uses enormous nationwide data sets and advanced statistical methods to provide more insight on the potential effects of several variables, including some linked to climate change, on honey bees. Their findings show that colony loss in the U.S. over the last five years is primarily related to the presence of parasitic mites, extreme weather events, nearby pesticides, and challenges with overwintering. The researchers worked with many nationwide databases and used tools that allowed them to look at, among other things, colony losses across space and time. They found patterns in colony losses, varroa levels, and land use (including presence of pesticides) that vary from region to region and could impact beekeeper decisions on where they place colonies and how they care for them. Hopefully, commercial beekeepers who move colonies across regions may be able to dig in for details that may help them preserve their stocks. [More info]

A new study led by Penn State researchers uses enormous nationwide data sets and advanced statistical methods to provide more insight on the potential effects of several variables, including some linked to climate change, on honey bees. Their findings show that colony loss in the U.S. over the last five years is primarily related to the presence of parasitic mites, extreme weather events, nearby pesticides, and challenges with overwintering. The researchers worked with many nationwide databases and used tools that allowed them to look at, among other things, colony losses across space and time. They found patterns in colony losses, varroa levels, and land use (including presence of pesticides) that vary from region to region and could impact beekeeper decisions on where they place colonies and how they care for them. Hopefully, commercial beekeepers who move colonies across regions may be able to dig in for details that may help them preserve their stocks. [More info]

Bumblebee Hyperventilation and Native Pollinator Loss?

At the January meeting of the Society of Integrative & Comparative Biology, Iowa State researcher Dr. Eric Riddell presented evidence that bumblebees, which face most if not all of the challenges that impact honeybee health, are forced by climate change into hyperventilation behavior which burns more energy and reduces the likelihood of survival. Riddell wanted to understand why climate change has dissimilar affects on different bee species. A global change biologist at Iowa State University, he and his colleagues studied queens belonging to the black and gold bumble bee (Bombus auricomus), a species in decline, and the common eastern bumble bee (B. impatiens), which is strong. The queens were placed in temperature controlled glass tubes and their respiration was tracked. After three days at higher temperatures, the black and gold bumbles (whose respiration increased from once an hour to once a minute) died at twice the rate of Eastern bumblebees (who increased from once an hour to once every ten minutes). Riddell will apply this research to additional species to determine whether this is could be a general pattern within native pollinator loss. [More info]

At the January meeting of the Society of Integrative & Comparative Biology, Iowa State researcher Dr. Eric Riddell presented evidence that bumblebees, which face most if not all of the challenges that impact honeybee health, are forced by climate change into hyperventilation behavior which burns more energy and reduces the likelihood of survival. Riddell wanted to understand why climate change has dissimilar affects on different bee species. A global change biologist at Iowa State University, he and his colleagues studied queens belonging to the black and gold bumble bee (Bombus auricomus), a species in decline, and the common eastern bumble bee (B. impatiens), which is strong. The queens were placed in temperature controlled glass tubes and their respiration was tracked. After three days at higher temperatures, the black and gold bumbles (whose respiration increased from once an hour to once a minute) died at twice the rate of Eastern bumblebees (who increased from once an hour to once every ten minutes). Riddell will apply this research to additional species to determine whether this is could be a general pattern within native pollinator loss. [More info]

Honeybees in Urban Areas May Be A Threat to Wild Species

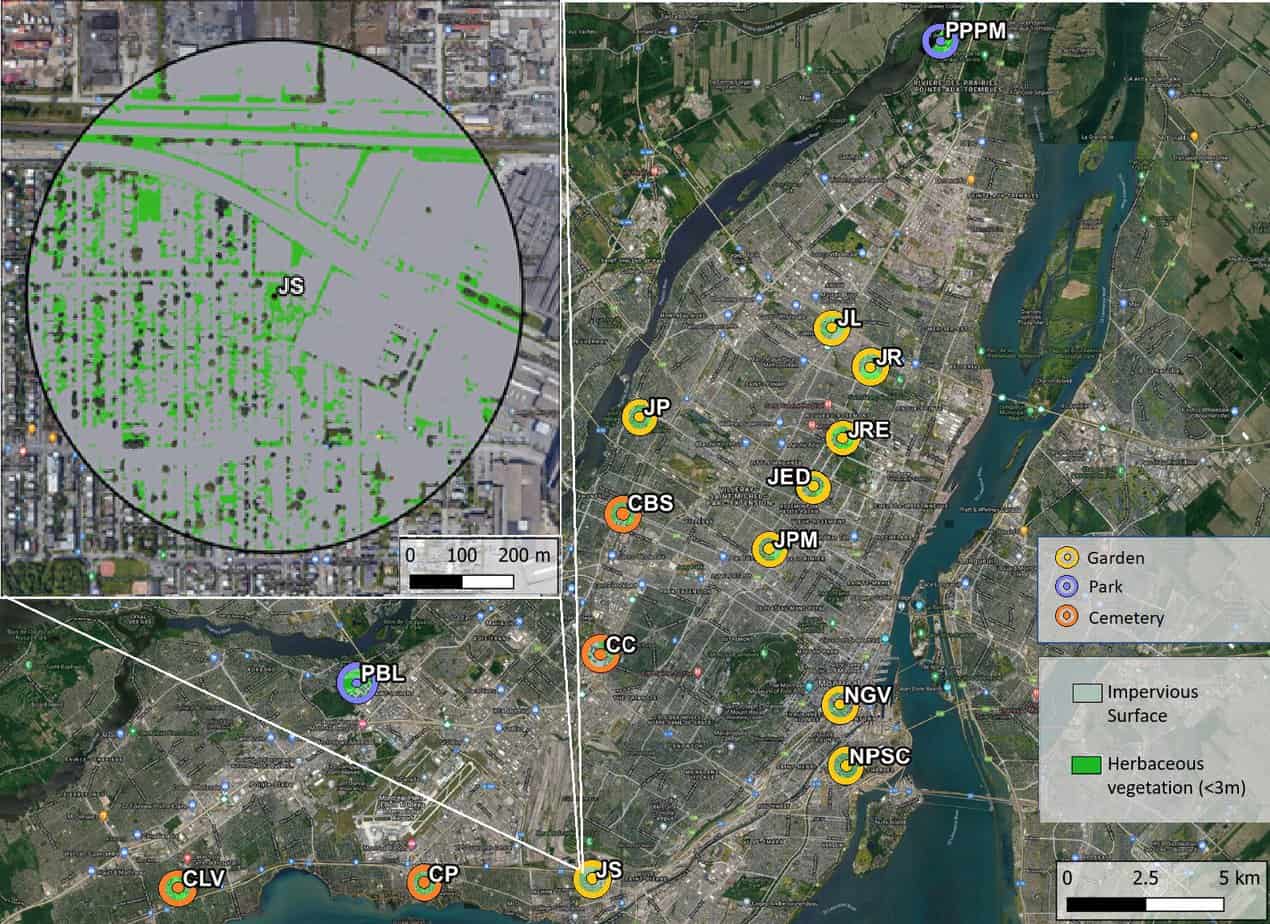

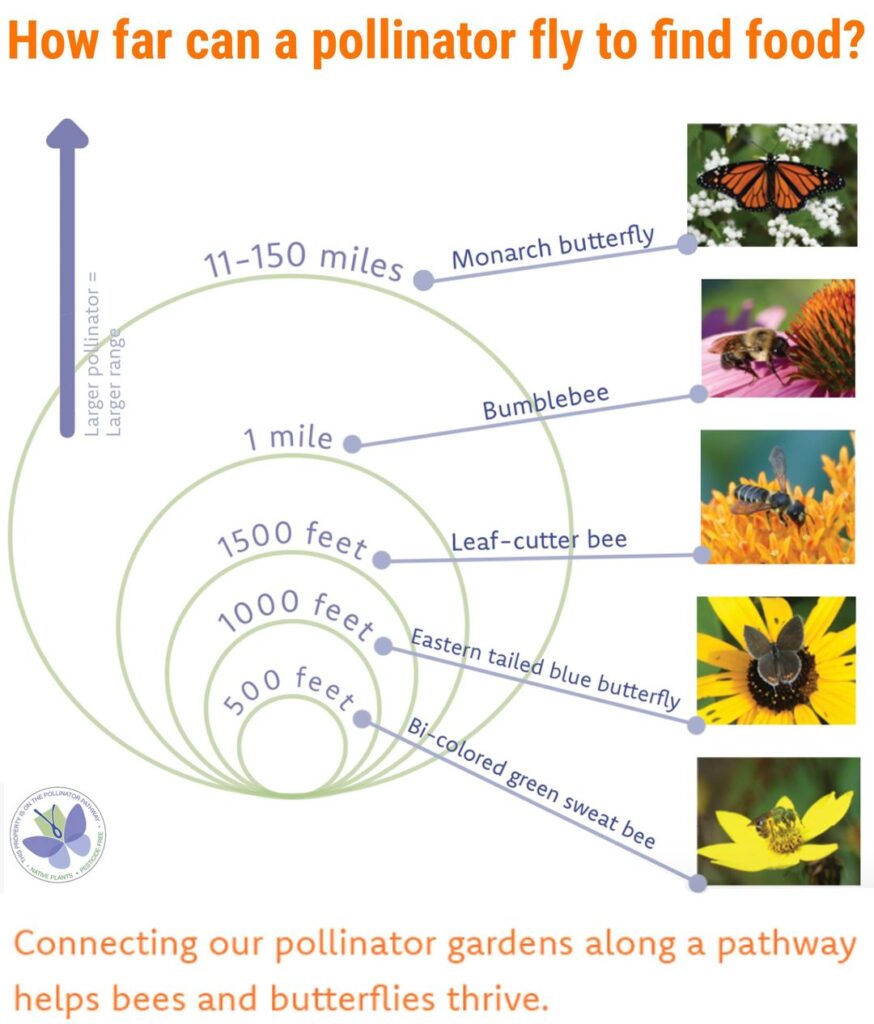

A study published February 3rd in PeerJ - Life and Environment finds a decline in the richness of wild bee species after the influx of large quantities of managed bee colonies to the Island of Montreal. "Richness" indicates the number of species present, and does not measure the actual abundance within each species. This study follows similar research in Berlin, Munich, Paris, and elsewhere. The main negative impacts of urban bees include forage competition and pathogen transmission. In Montreal, researchers were able to compare data from 2013, before the large increase in popularity of urban beekeeping, and 2020, after the establishment of almost 3,000 managed colonies in the city. Smaller species appear to fare the worst in competition with honey bees, probably due to their limited foraging range. The researchers recommen that "evidence-based beekeeping regulations [are] essential to ensure cities contain sufficient resources to support wild bee diversity alongside managed honey bees. [More info]

A study published February 3rd in PeerJ - Life and Environment finds a decline in the richness of wild bee species after the influx of large quantities of managed bee colonies to the Island of Montreal. "Richness" indicates the number of species present, and does not measure the actual abundance within each species. This study follows similar research in Berlin, Munich, Paris, and elsewhere. The main negative impacts of urban bees include forage competition and pathogen transmission. In Montreal, researchers were able to compare data from 2013, before the large increase in popularity of urban beekeeping, and 2020, after the establishment of almost 3,000 managed colonies in the city. Smaller species appear to fare the worst in competition with honey bees, probably due to their limited foraging range. The researchers recommen that "evidence-based beekeeping regulations [are] essential to ensure cities contain sufficient resources to support wild bee diversity alongside managed honey bees. [More info]

And BOBs Your Tenant: Honeybee Hives as Osmia Incubators

Among the many "secrets" that beekeepers often chew on privately is the fact that many other species actually work longer and at lower temperatures than "our girls." The floral fidelity (basically, pollination efficiency) of honeybees makes them critical to agriculture, but they may have an additional collaborative role available!

Among the many "secrets" that beekeepers often chew on privately is the fact that many other species actually work longer and at lower temperatures than "our girls." The floral fidelity (basically, pollination efficiency) of honeybees makes them critical to agriculture, but they may have an additional collaborative role available!

A USDA/ARS team led by Lindsie McCabe looked at the use of Osmia lignaria on orchard crops: these bees require artificial warming in order to be available in time for crop blooms, and the process is time consuming and inefficient. Instead, the team created the Hivetop Incubator (HTI): an invention that creates a space on top of a honey bee hive which allows heat to rise through ts mesh bottom to incubate cocooned O. lignaria adults.

The team found no significant differences between the internal temperatures of A. mellifera colonies with and without HTIs and no impact on A. mellifera food storage or brood production. Osmia lignaria in hive-heated HTIs emerged 3× faster than bees in unheated HTIs.

[Return to February 2023 BeeLine newsletter]